We’re all trying to do good work

We work in distributed product development teams where English is our daily language for discussing design decisions, timelines, and deliverables. Everyone is performance-oriented and wants to ship something valuable. We have designers who understand customer needs, product people who balance competing priorities, engineers who build solutions, and stakeholders who need to plan resources and timelines. On paper, this should work smoothly.

But it doesn’t.

When words mean different things

Stakeholders are worried about unknown dependencies, unclear timelines, and uncertain outcomes from the UX team’s work. They question designers’ assessments and challenge their estimates. When design plans are too general or poorly articulated, the magnitude of this issue multiplies. Stakeholders find themselves asking, “Why are we still researching when we should be building?” or “Can’t you just design one screen?” They’re trying to keep promises on planned delivery dates, and design work often feels like an unpredictable black box.

On the other side, designers are frustrated. They’re tired of repeatedly teaching, explaining, and convincing product teams about the need for various design activities. They feel their expertise is questioned. They hear stakeholders say things like “We don’t need research for this project,” or “You’re always researching,” or “I need to research this,” and these statements reveal fundamental misunderstandings about what design work actually entails.

Both sides blame the other—for ignorance, for skewed motivations, for not caring enough about delivering value. But the real problem is simpler: we’re not speaking the same language. And while both sides contribute to this confusion, designers are the ones who must fix it—because we’re the ones who created the specialized vocabulary in the first place.

Designers, we need to look in the mirror

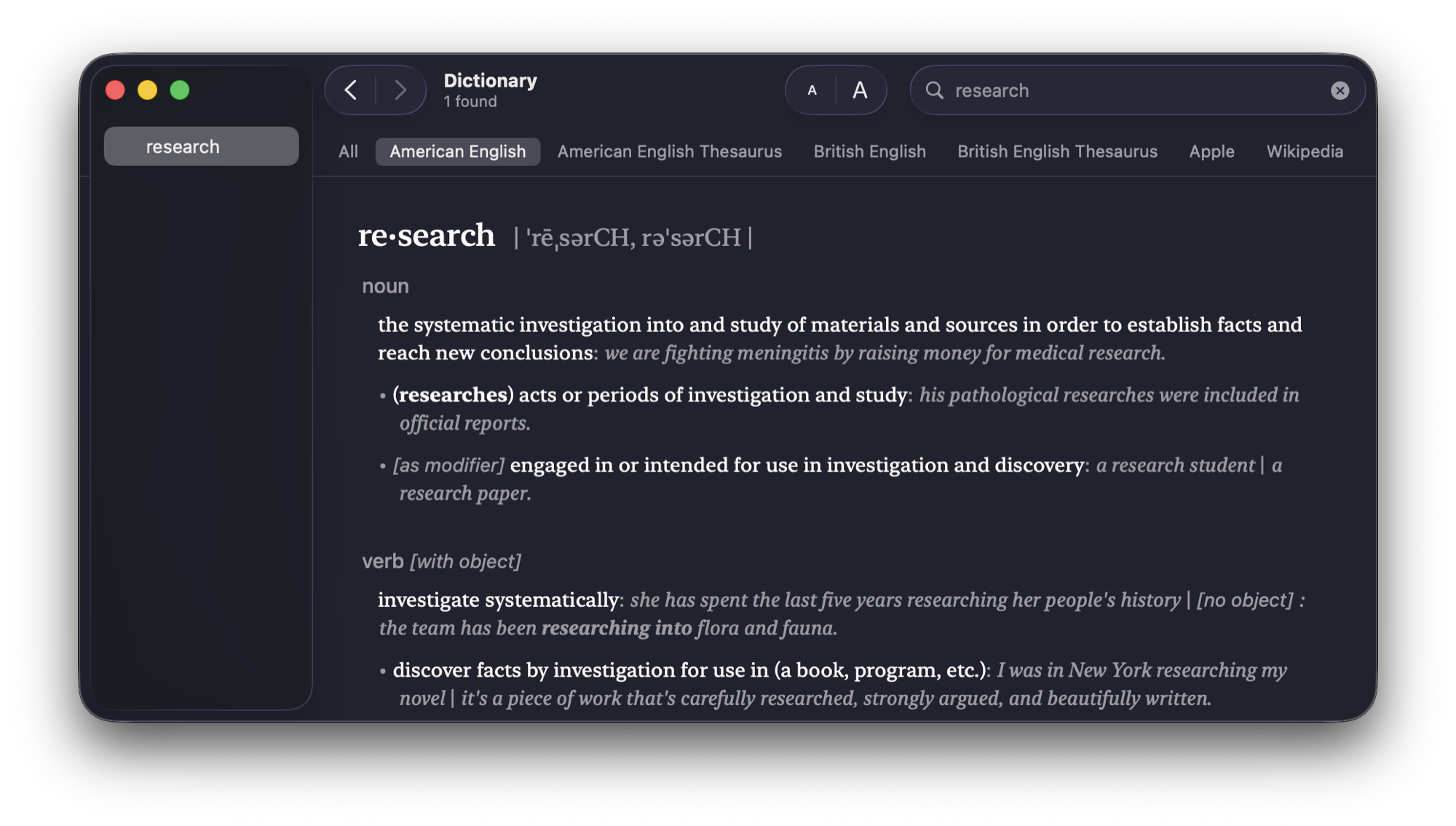

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: this is primarily our problem to solve. As designers, we use terms like “research,” “testing,” “validation,” “discovery,” and “exploration” without much thought to how they land with our colleagues. We know what we mean because we’ve been trained in these distinctions. But to someone outside our field – or even to junior designers on our own team – these terms blur together into an incomprehensible soup.

When a designer says “I need to research this” while meaning “I need to learn how this technical system works,” we dilute the meaning of research. When we talk about “testing” without specifying whether we mean usability testing, A/B testing, or technical QA, we create confusion. When stakeholders hear “one screen” and we’re actually designing a complete customer journey across multiple channels and states, we’ve failed to communicate scope. When everything becomes “research,” nothing is research.

This isn’t about stakeholders being ignorant or unwilling to understand design. This is about us not taking responsibility for making ourselves understood. We expect others to learn our language, but we haven’t simplified or aligned that language – not just for them, but for ourselves. If junior designers on our own team struggle with these distinctions, how can we expect stakeholders or engineers to grasp them intuitively?

The solution isn’t to educate everyone else. The solution is to change our own behavior.

Understanding the double diamond

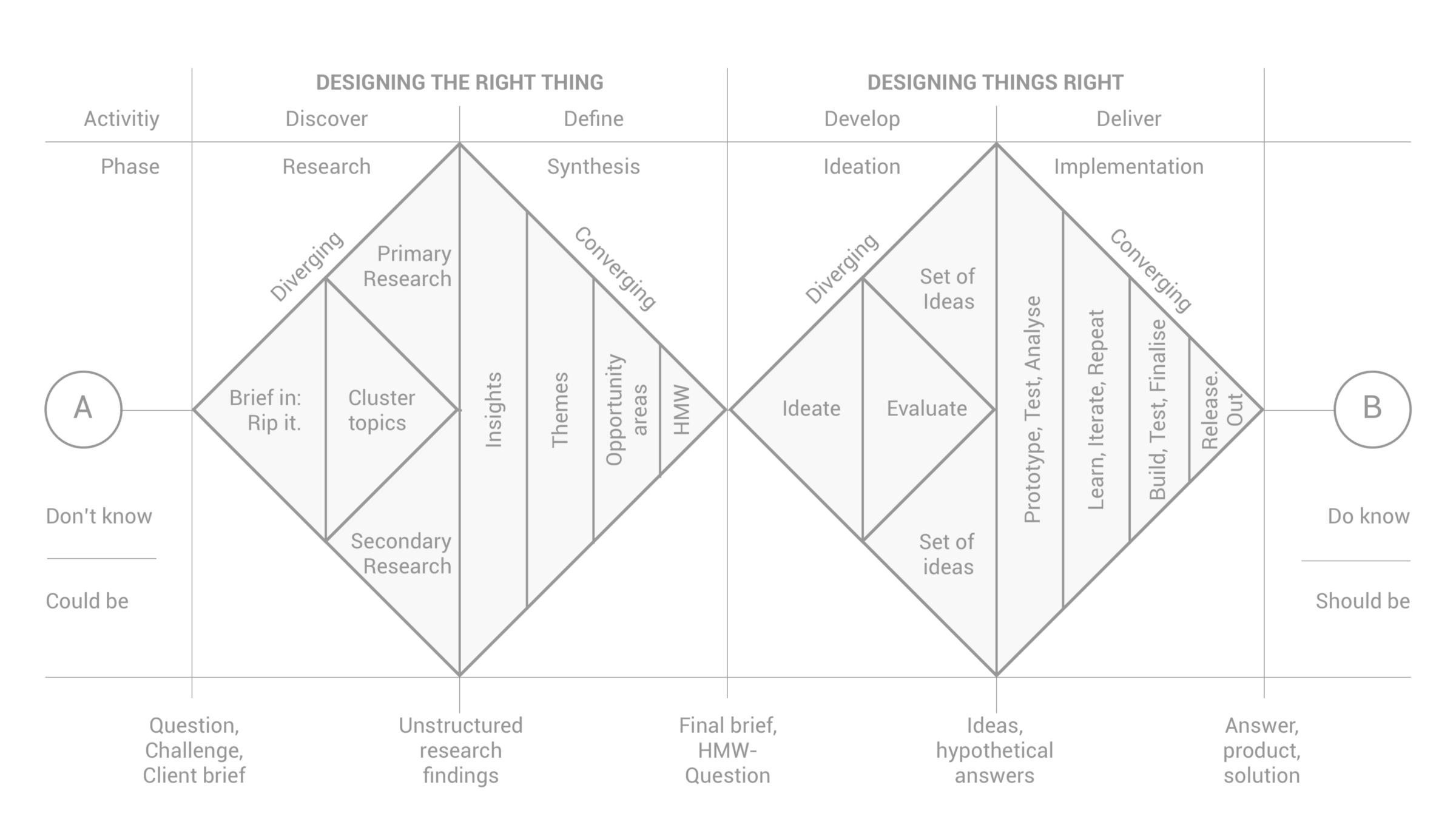

Before we can align our language, we need to understand the underlying framework that organizes design work. The double diamond1 — a model that visualizes the design process—divides our work into two distinct spaces: Designing the right thing (problem space) and Designing things right (solution space). Each space contains two phases, creating four phases total: Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver.

Most confusion happens in the problem space (Discover and Define phases). This is where designers explore customer needs, identify the real challenge, and define what problem we’re actually solving. Non-designers genuinely struggle to distinguish between these two phases. People are performance-oriented. We instinctively jump to solutions. We assume we know what the problem is and want to start building immediately. This is precisely why our team facilitates two-day service design training sessions – to give colleagues firsthand exposure to real customer needs through interviews and observation. After watching a customer struggle with something we assumed was simple, product people stop saying “We already know what users want.”

Product teams have deep product knowledge on technical and business levels, but from a customer understanding perspective, we – as an organization – often lack clarity. The question “What’s the real challenge here?” is rarely answered with depth from the customer’s perspective. We skip the problem space and jump straight to the solution space – and this is where projects go wrong.

The solution space (Develop and Deliver phases) is where we create, test, and implement design solutions. But even here, language fails us. When stakeholders talk about “designing only one screen,” they’re thinking about a single interface element. Designers, however, are focused on designing a complete customer journey – a job to be done. This often consists of a series of steps, changing component states, and a significantly different information architecture depending on the channel: internet bank, mobile app, or internal tools.

One screen? No. We’re designing an entire experience.

Advance your career and leadership

Subscribe and get actionable insights sent to your inbox.

- Practical frameworks from years of experience

- Case studies and implementation guides

- Career development strategies for professionals

I respect your privacy. I will never share your email, and you can unsubscribe anytime.

This is why our terminology matters so much. If we can’t clearly articulate which diamond we’re in – problem space or solution space – and what type of work each phase requires, we’ll continue to confuse everyone, including ourselves. Let’s define the language we actually need.

The language we need

If we want to improve collaboration and establish design expertise, we must commit to using consistent, simple language. Here are the definitions we need to align on—both within our UX team and with our stakeholders.

Problem Space vs. Solution Space

| Term | What It Means | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Space (Discover + Define) | Understanding what challenge customers actually face and why it matters to them and the business | A clearly defined problem statement, customer insights, and strategic direction |

| Solution Space (Develop + Deliver) | Creating, testing, and implementing design solutions that address the defined problem | Designed solutions, validated prototypes, and implemented features |

ELI52: Before we build anything, we need to understand whose problem we’re solving and what that problem really is. Once we know the real problem, we design options, test them with users, and build the right one.

Four critical terms

1. Generative research (problem space - Discover)

What it means: Exploratory work to uncover customer needs, behaviors, and pain points we don’t yet understand.

In simple terms: We’re asking “What don’t we know about our customers?” to discover opportunities.

| Methods | Output |

|---|---|

| User interviews Contextual inquiry Diary studies Ethnographic observation | Insights Opportunity areas Unmet needs |

When to use it: Early in the project, before defining solutions

Note on strategic research: Some generative research projects are long-term strategic initiatives that produce customer journeys, personas, mental models, and comprehensive reports. These strategic research outputs inform business decisions for years and provide a foundational understanding across the organization.

2. Evaluative research (solution space - Develop)

What it means: Testing whether our design solutions actually solve the problem and meet user needs.

In simple terms: We’re asking “Does this design work for our customers?” to validate our direction.

| Methods | Output |

|---|---|

| Usability testing A/B testing | Validated design decisions Identified friction points |

When to use it: After we have designed concepts to evaluate

3. Usability testing (solution space - Develop/Deliver)

What it means: A specific type of evaluative research where users interact with a design to complete tasks.

In simple terms: We watch real users try to use our design to see what works and what’s confusing.

| Methods | Output |

|---|---|

| Moderated task-based testing Unmoderated remote testing | Task success rates Usability issues Improvement recommendations |

When to use it: When we have something tangible (wireframes, prototypes, or live products) to test

Critical distinction: This is NOT generative research—we’re not discovering new problems, we’re evaluating solutions.

4. Validation

What it means: Confirming that an assumption, hypothesis, or solution is correct or viable.

In simple terms: We’re checking if our bet is worth pursuing or if our solution actually works.

Who uses it:

- Innovation teams validate business opportunities

- Designers validate problem definitions and solution directions

- Product teams validate features meet requirements

When to use it: Throughout the process, but the type of validation changes (business validation ≠ design validation ≠ technical validation)

Terms to avoid or use carefully

Research" (without qualifier)

Problem: Too vague—could mean anything from Googling competitors to conducting 20 user interviews.

Solution: Always specify the type: generative research, evaluative research, competitive research, desk research.

Never say: “I need to research this” (about learning a tool or reading documentation)

Instead say: “I need to explore this” or “I need to learn about this”

“Testing” (without qualifier)

Problem: Could mean usability testing, technical QA testing, A/B testing, or validation.

Solution: Be specific about what you’re testing and why.

“One screen”

Problem: Oversimplifies the design scope and ignores the complete customer journey.

Solution: Framework as “jobs to be done” or “customer journeys” that may include multiple screens, states, and channels.

What we must do differently

Aligning our language isn’t just about creating a glossary. It’s about fundamentally changing how we communicate about our work. It’s about taking responsibility for being understood. It’s about recognizing that if our stakeholders don’t understand what we’re doing, that’s a failure of communication on our part — not a failure of understanding on theirs.

Here’s what this looks like in practice.

Involve stakeholders early and often

Late involvement equals a lost game. When designers learn about a project as it’s starting – after planning discussions have already happened – we enter a situation where the real problem may not have been fully explored. Teams might draw inspiration from competitor examples or adopt a “make it beautiful” approach. Awareness of the value of research hasn’t arrived yet, and the organization wastes time and effort on surface-level improvements without capturing real opportunities.

If researchers and designers are involved in initial project planning discussions – ideally when the business opportunity is identified but before any solutions are proposed – we have time to evaluate, plan, and communicate the reasoning for various design activities. This means being in the room when someone first says, “We need to improve customer retention,” not when they say, “We need to build a loyalty program.” We can shape the conversation. We can ensure the problem space is explored properly. We can set realistic expectations about timelines and deliverables. This is where design briefs become essential – they’re the tool that aligns everyone before work begins.

Early involvement isn’t just about design quality. It’s about establishing credibility and demonstrating leadership.

Make design work visible and tangible

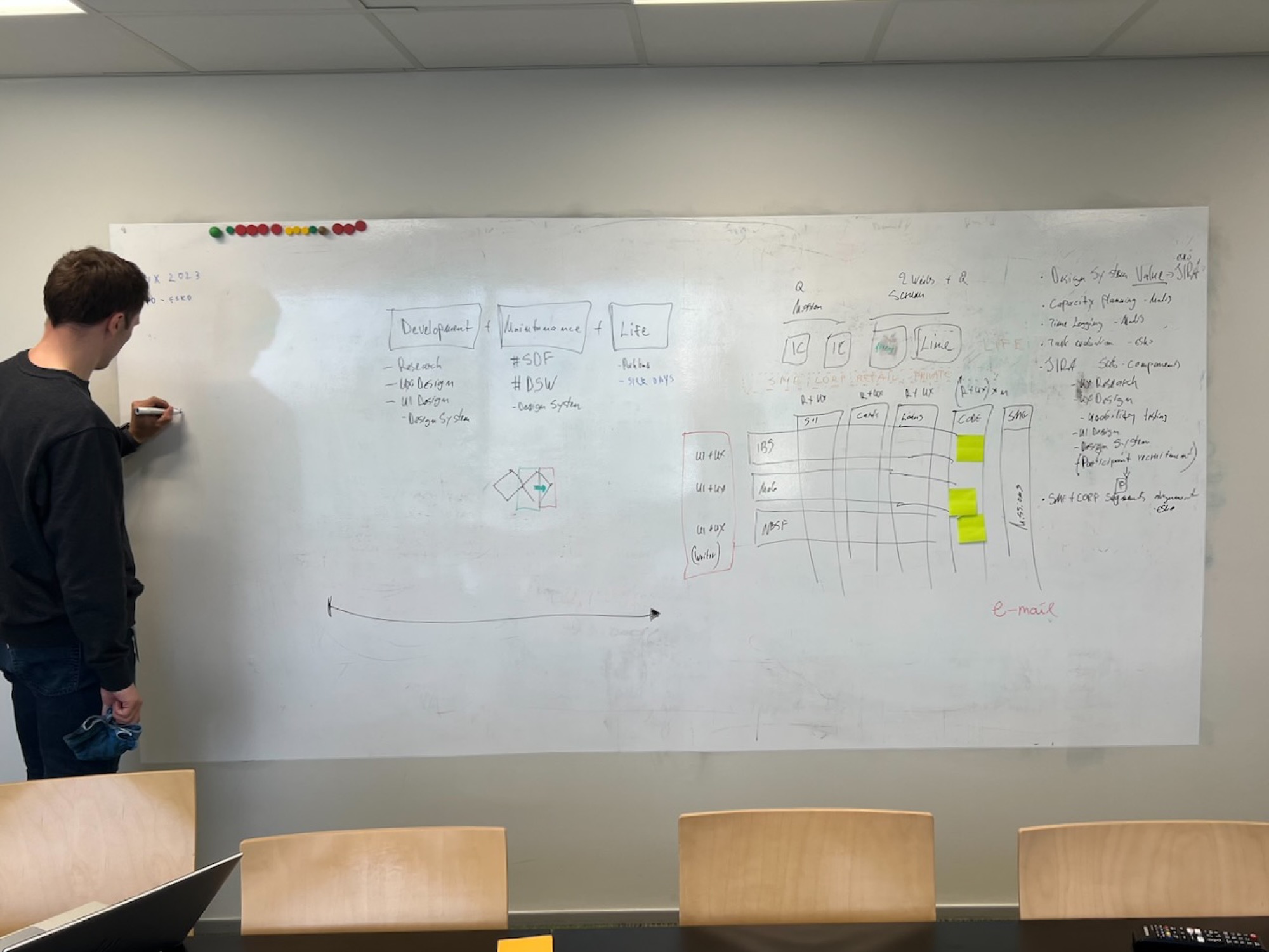

If a UX team member only talks about the process without expressing it in any tangible way, each person imagines their own interpretation. This is a major issue. When we sketch a timeline, create a Gantt chart with phases and dependencies, or outline rough completion dates, we transform abstract concepts into shared understanding. One of the key improvers of a product team’s UX maturity is simply making design work visible. Show the steps. Show the collaboration points. Show what’s happening and when.

We use design briefs to facilitate this communication. A design brief defines the project’s purpose and outlines goals and metrics for evaluating the outcome, not just design outcomes. It also contains a timeline of design work. In planning mode, this might be a rough sketch that eventually translates into a comprehensive project roadmap in JIRA. The design brief serves as both a communication tool and an agreement – outlining what’s in scope, what’s needed from the UX team, and how we’ll arrive at the best result given our constraints.

If a project includes research, we prepare a research plan with all materials, communicate it clearly, and align it with the product team. The more transparency we create, the higher the collaboration and success for the product and business.

Use consistent language in every interaction

This is where discipline matters. Every time we talk about design work, we must use the terminology we’ve defined. Not “research,” but “generative research” or “usability testing.” Not “testing,” but specifically what kind of testing. Not “one screen,” but “the complete journey for this job to be done.”

This feels pedantic at first. It feels like overkill. But repetition creates understanding. Consistency builds trust. When stakeholders hear us use the same precise language repeatedly, they begin to adopt it themselves. And when they adopt our language, they adopt our mental models—they start to think about design the way we think about design.

Teach through action, not just explanation

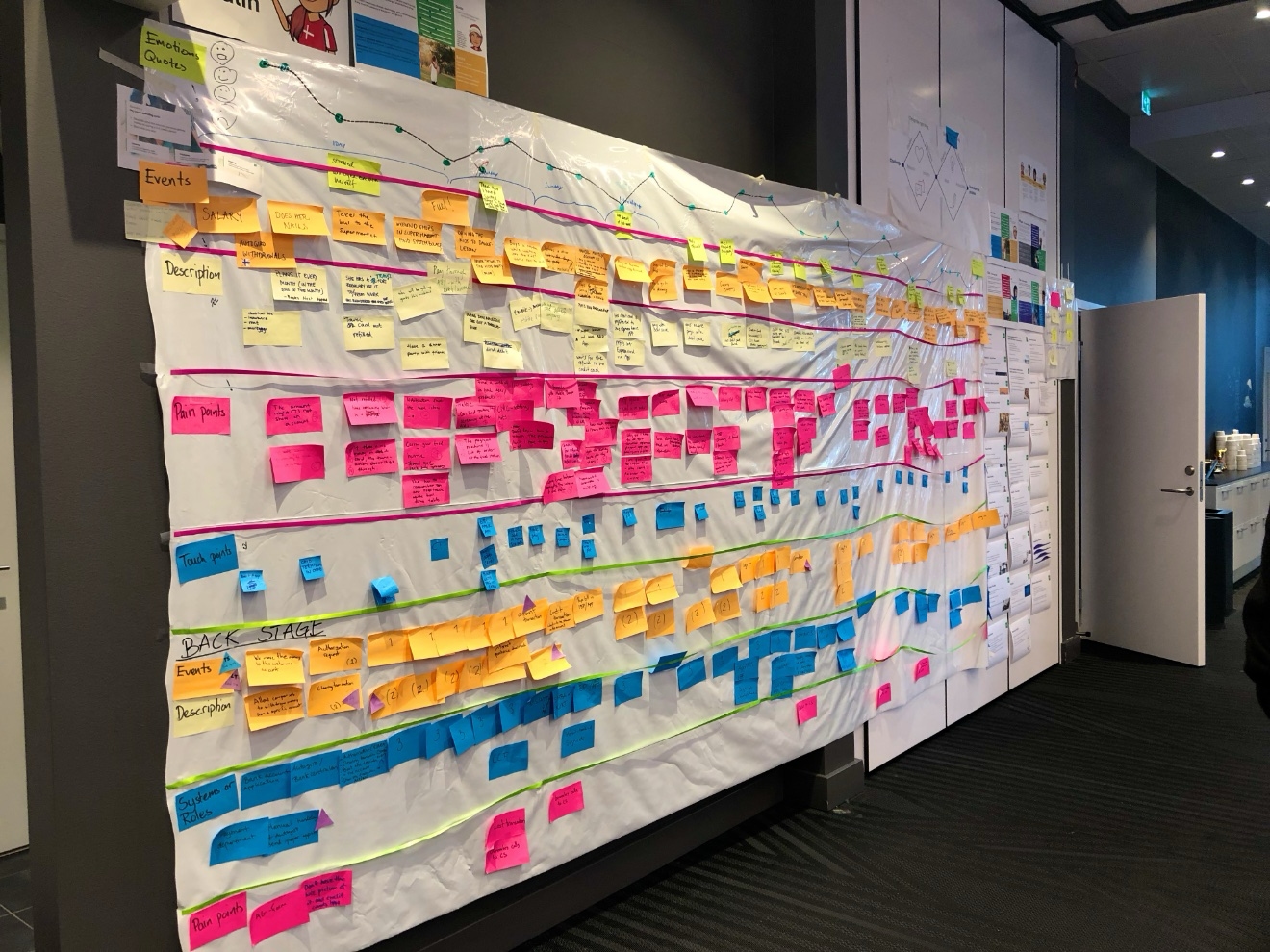

Words matter, but experience matters more. This is why we facilitate two-day service design training sessions where colleagues conduct interviews and usability tests themselves. When product people watch real customers struggle with a prototype, they understand the value of usability testing viscerally, not just intellectually. When engineers hear customers describe needs that contradict their assumptions, they understand why generative research matters.

We can define terms all day long. But until people experience the difference between generative research and usability testing firsthand, the distinction remains abstract. Without this experiential understanding, stakeholders will continue to question why we need “so much research time” and push us to “just test with users” when we haven’t even defined the problem yet. Create opportunities for stakeholders to participate in design activities. Let them observe research sessions. Invite them to synthesis workshops. Make them co-creators, not just recipients of design deliverables.

When they see the work, they understand the language.

The language we use shapes the work we do and the value we deliver. It’s time we get serious about both.

Nessler, Dan. “How to Apply a Design Thinking, HCD, UX or Any Creative Process from Scratch.” Digital Experience Design, February 7, 2018. https://medium.com/digital-experience-design/how-to-apply-a-design-thinking-hcd-ux-or-any-creative-process-from-scratch-b8786efbf812. ↩︎

Reddit. “r/explainlikeimfive.” Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/explainlikeimfive/ ↩︎